Henriette Noermark

Boris Berlin & Nigel Majakari in dialogue

Being the first designer to join the Ca’lyah journey, which he calls just crazy enough and a whispering game, Boris Berlin (b. 1953) travelled to India with founder Nigel Majakari to research, evolve and set in motion the Tranquebar edition. Comprising a chair, a stool and tables with more pieces in the pipeline, the series resembles the vivid colours of India, the ambitious visions of the brand and the craftsmanship that connects us.

Henriette: I am interested to hear how this collaboration began and what enticed you to working together?

Boris: When Nigel explained his somewhat crazy idea to our mutual acquaintance, he mentioned me as a right type of designer to take on a project like that. And then Nigel called me, came to the studio and seduced me with his idealistic project, that seemed to be a hardly realizable, yet amazingly good idea. It sounded different and crazy enough to be part of, I thought.

Henriette: He told you about a new company with a vision, but no portfolio yet. How did you know that these bold ideas were good?

Boris: This is exactly what attracted me, my curiosity took over. Moreover, the older I get, the more I want to work with people whom I like – and I liked both the person and his ideas. His visions were ambitious, and with my qualifications I could contribute with knowledge and products that could change something rather than just thinking in commercial strategies. I looked forward to being part of the different, more open and inclusive, structure of the Ca’lyah project.

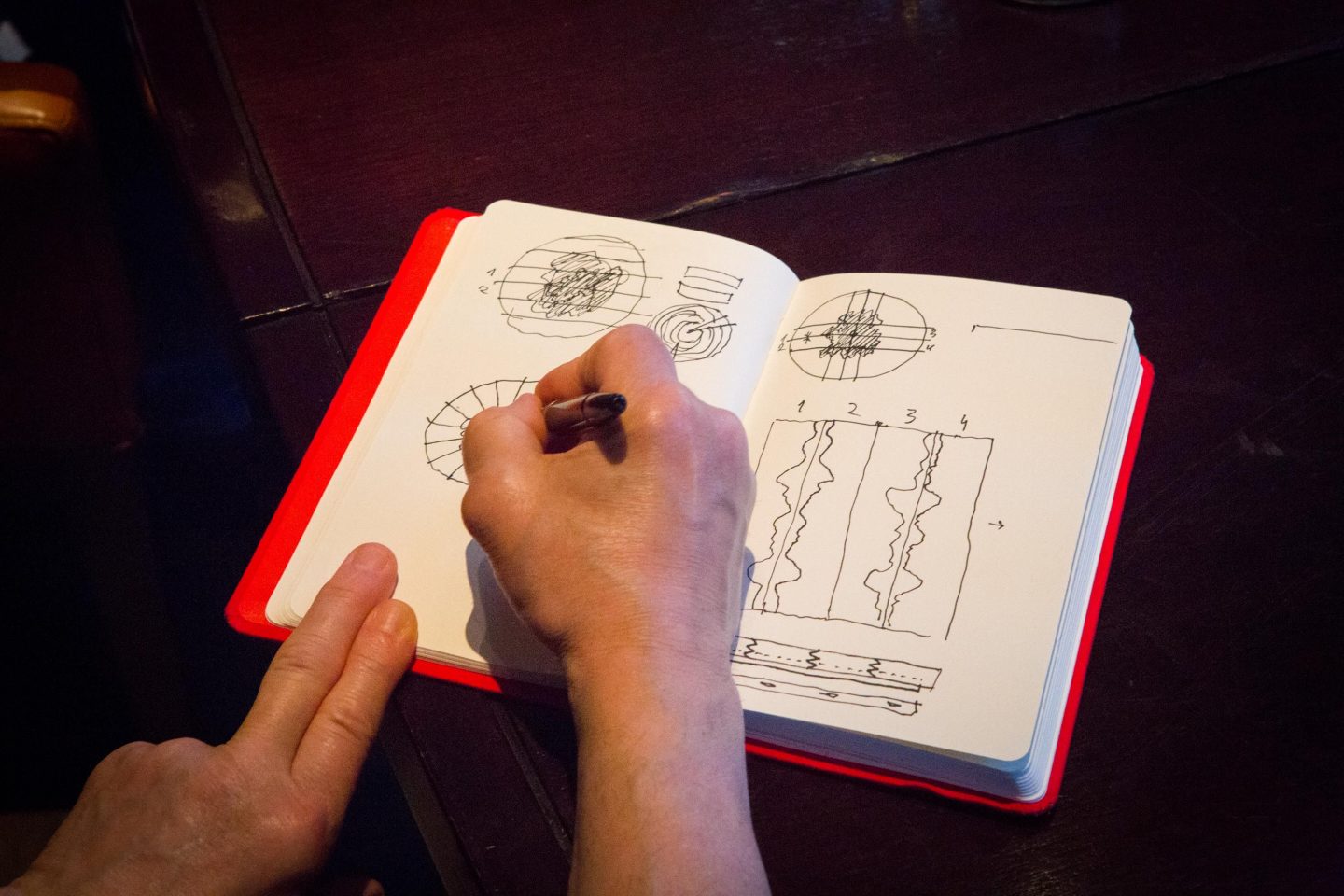

To see my design interpreted, transformed by craftsmen – and sometimes misunderstood – was like the telephone game, where the message goes from one to the next and onwards, and then hearing the, now changed, result in the end. It is fantastic. I really want to hear what comes out in the end.

Henriette: Nigel, was it a crazy idea?

Nigel: At the first meeting I recall having with Boris at his studio, I explained that I had spent two years with a local team in South India visiting the workshops of furniture craftsmen, village by village, inviting passionate and skilled carpenters to group meetings to understand their challenges and opportunities for their craft and future of the artisanal industry. We built a network of over 8000 mainly rural carpenters. We talked about environmental issues and completed the first of its kind process taking micro wood furniture enterprises through the Forest Stewardship Council certification process (FSC). While it was clear that there was a tradition lasting hundreds of years of wood and stone craft and a desire for innovation exists, there are, realistically, gaps in knowledge, skills and an ecosystem of collaborators to step forward. This makes the barriers to accessing new markets even harder to breakthrough. However, the ingredient that is most absent, yet critical for progress and change are stories of craftsmen and women who have scaled the heights of those barriers and broken through.

Henriette: The vision behind Ca’lyah is to create change through evolving that ecosystem?

Nigel: Yes, the bold, audacious and perhaps crazy dream of Ca’lyah is to create opportunities for craftsmen like carpenter Ganesh, master stonemason Mr. Mahdevan along with his three sons in Tamil Nadu or Mrs. Dickey, a Tibetan hand loom weaver and wool dyer living in Nepal.

It is really about bringing people together from different cultures, crafts, and experiences to craft exceptional objects that will echo beautiful stories throughout homes and public spaces. To make this a reality by creating shared value for everyone involved, I needed find unique kind of designers and creatives to be involved. That is why I reached out to Boris and asked him to be involved. He immediately said yes, and we invited master carpenter of PP Møbler, Søren Holst Pedersen, to join as well.

Boris: Do you know the story of the tree?

Henriette: No, please share.

Boris: When a child is born, the family plants a tree. If they have more money, they plant several. It is teak. There are many kinds of teak and this is local. When the child is ready to get married, they cut the tree, then parents carry it on their shoulders to the local carpenter who will make a double bed from it. If there is some timber left, he makes a wardrobe. If there is more timber left, he can turn it into a daybed. And this is their wedding present – and when in this double bed the next child is conceived, they plant a new tree. When Nigel told me this story I was sold, it is really that simple. I knew nothing, just went with open eyes – no ideas, no nothing. I had not been in India before that. It was indeed very interesting and completely new to me.

Henriette: The story of the family and tree seems to address the issue of sustainability in an unusual way?

Nigel: I think it gives us insight to learn from. Context shapes our understanding, our awareness of ideas and priorities, this is true about sustainability. Take a rural craft family in Tamil Nadu where we built our network: They pursue their craft with a daily struggle to feed their families and keep a roof over their heads. The circumstances of life demand frugality, recycling, and traditionally what is known as Jugaad innovation – which could be anything from utilizing home-made bio fertilizers to mechanical devices made from scrap metal and aging parts. Many of their lives are actually defined by the struggle for sustainability. Our role at Ca’lyah is to listen and understand. Then in the context of trust, work together to create stability and introduce new technologies and methods that ensure minimal impact on the environment.

Henriette: Boris, you said “it is first of all a language, a means of communication.” I am curious to know more about the language you are referring to.

Boris: Design is a language. A designer sends their ideas to a craftsperson, whose job is to read, interpret and ultimately create and transform the final product from a sketch. They have to read your message in the bottle, so the message needs to be clear – especially when sending the bottle to a country which is 7,500 km away from the studio, where they speak a different language as well.

An example was when designing the ornament for the Tranquebar tables: I drew it, handed it over and initially expected to get something else back. I was hoping it would be as with a partiture, a musical score which is the same on paper but performed individually and slightly different. The first prototype was my notes scratched onto the stone rather than being three-dimensional, so now I am cutting it instead of drawing it, and I hope they will take their creative freedom and interpret it in their own way. Everything in our life is about sending a message – in this case a drawing – and getting a reply, an answer, sometimes not the one we expected. It is the quintessence of design process. Designers, on the contrary to craftsmen, are working with a whole chain of other people taking part in the creation process so you must be able to mediate your message. Apart from this the designer has a different role than the craftsman. Craftsmen look backwards – they are keepers of tradition. While designers are destructors or disruptors. The designer questions and brakes tradition, craftsman passes a tradition on through generations.

Henriette: So you send references back and forth, and understand each other’s tools and skills?

Boris: Yes, and it really evolves. During my visits to Tamil Nadu I learned that many of the craftsmen are part of the Vishwakarma community or caste. There are similarities to the European craft guilds that emerged out of the medieval period. It was clear that industrialization and demands for cheaper products are affecting the craftsmen and their status in the community. Nevertheless, their skill and art in general is everywhere to be found in India, it is in the air. Indian housewives draw a mandala with chalk outside the house every morning to protect the house. If washed out by rain, she draws it again and this is a daily practice that you see everywhere.

Henriette:Mandalas and ornaments on rickshaws; tell me about the role of the ornamentation versus the design itself?

Boris: Ornamentation comes to them naturally; it is a signature. They cannot leave a square centimeter of surface without covering it with ornaments. An ornament is functional – it is a protection of the house, of the person. Even under the trucks there are ornaments… so I closed my eyes and drew. The simplicity of the general shape is crucial though – the design needs to be strong enough to take the ornamentation. Normally, I design simple minimal items first and foremost starting with a body, a frame, a base, a background. That was the initial idea: to design these bodies and then the ornamentation would be applied. When you visit the masonries, it is interesting to see how they sculpt temple statues – the sculptural language depicting the body is simplified and generalized. There are no muscles, no tension, it is a generalized etui – but then comes the ornamentation with thousands of decorative elements. Even if it is staying on the top of a temple, it is made with peculiar detailing.

Henriette: How is the Tranquebar Chair different from other chairs on the market?

Boris: I stopped making chairs 20 years ago. I am not doing chairs anymore, there are enough chairs.

Henriette: You just made a chair?

Boris: No. You think it is a chair. But it is not.

Henriette: Then what is it?

Boris: It is a story about a chair – there are so many chairs in the world. And many people who make chairs and try to make the best chair, but that is not my aim. It is my sketches from the trip rather than a chair. It is not that I have seen this thing there, it is like closing my eyes and what I remember: The silhouettes, the geometry, and shadows.

Henriette: It is a way of communicating through a chair – and the round shapes revolve from the shapes you’ve seen?

Boris: Exactly, Henriette. It is full of mandalas, the circles. Probably this is where it comes from. The colours can be anything. Colour is not my work, I make a body, that has to be able to take any colour or any kind of “tattoo” without being destroyed.

Nigel: The Tranquebar chairs, like the other objects in this edition, have physical properties and serve a practical function. But they are also the realization of values, experiences and emotions of the people whose lives were dedicated to creating them.

Henriette: This sounds rather different from a traditional furniture design company.

Nigel: My ambition for Ca’lyah is not to be a furniture company, but rather a curator of stories that help customers express their love of fine design, care for the environment, and desire to make a positive difference in the world. I am convinced that there is so much more pleasure and joy we can experience in our homes and changing working environments when we reimagine furniture in this way.

Henriette: So, what will the future hold, how will this collaboration evolve?

Boris: We also have a project in motion right now exploring traditional textile crafts and looking at ways of working with silk. These things take time, and of course there are bumps on the road in this day and age, but they all make sense – some issues will be solved, new ones will arrive to be solved – that is life and that is what the Ca’lyah project is about, I believe.

Nigel: Navigating Covid-19 has been brutal on our craftsmen, -women and their families. We are working hard to try and help them bounce back. We have used the time in Copenhagen to develop some new products for the Tranquebar edition and our long-term plan with Boris is to establish a Scandinavian-Indian craft academy in Chennai. With the support of our customers, industry and foundations this will help equip a new generation of skilled craftsmen and -women for the future.